HOME • ASSISTED PUBLISHING • JOIN MAILING LIST

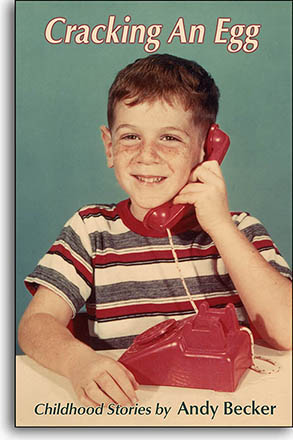

A collection of witty & nostalgic vignettes from a well-lived childhood

“In this charming compilation of vignettes, Andy Becker shares belly-laugh stories about growing up in the 50s and 60s. With a keen sense of irony he describes fond and not-so-fond memories: fishing with his Mom, Dad and siblings when smothered by mosquitoes; Thanksgiving Day when relatives squirted each other in the eye with lemons; and the annual Seder, when Andy studied rigorously to memorize all his lines. Becker includes fascinating scenes, such as when his grandfather, the owner of an upholstery factory, brought coffee and donuts to the workers who were all striking against him. A delight for readers of all ages, this engaging collection is not to be missed.” — E.C. Murray, Founder, Writersconnection.org

“Follow the adventures, mishaps and tribulations of a boy growing up in suburban America in the 60s. You will laugh, tear up, and sigh with nostalgia as you recall the days of playing with little green soldiers, jumping hedges, and going to the neighborhood bakery with Mom. This heartwarming book humorously recounts memories guaranteed to remind you of your own childhood.” — Kerry Stevens, author of Blood Ties

ANDY BECKER grew up in San Mateo, California during the 1950s and 60s. He is a writer and lifetime learner living in Gig Harbor, Washington. Cracking an Egg is a humorous and heartfelt memoir of early childhood experiences, vignettes that discuss conformity, rebelliousness, family relationships, fantasies, humiliations, gratitude and most of all, love. Andy is also the author of The Spiritual Gardener: Insights from the Jewish Tradition to Help Your Garden Grow —“With wry humor, earthy spirituality, and practical advice, lawyer and amateur gardener Becker tells the story of his own garden and entreats readers to plant, tend, harvest, and share their own soil in this fine debut.” — Publishers Weekly

Published by Tree of the Field Publishing in association with Fearless Literary • 130 pages, trade paperback with 22 B&W photographs • $12.95 • ISBN 978-1-7336698-1-8 • Available to the trade from Ingram

__________________________________________________

ORDER NOW

Order a signed copy with free shipping

from the author, OR:

__________________________________________________

CHAPTER 1

Peanut Butter Face

My mother was not happy: the local elementary school had accused my older brother of stabbing a fellow kindergarten student with a pencil. According to Mom, the more likely scenario was that the classmate was a sociopath who viciously stabbed him. She burned up the phone lines in the aftermath of the incident, but the matter was never resolved.

History shall record that Mom fought for her children like an Army Ranger scaling the cliffs of Normandy, even if no one ever photographed her waving the family flag. She demonized any reprobate in her child’s path. In addition to using the telephone as heavy artillery, she fumed full steam whenever one of her friends was kind enough to come over for coffee. My brother’s teacher was now on a par with the villains of history — Hitler, Mussolini, and all the Republican Presidents after Dwight D. Eisenhower. Fearless in meetings with the teacher, principal, or school board members, she dressed up for each confrontation in her own style of combat gear. Off went the pants and tennis shoes and on went the panty hose, skirt, and shoes that click-clacked on her way out of the house, emphasizing the seriousness of her purpose. Mom meant business.

I wasn’t really attuned to this battle because I was directing a different one. My little plastic army men were always engaged in combat on the floor, pummeling each other to smithereens using their tiny hands, arms and legs. Eventually, a favorite little soldier would be the clear winner of each fight.

But my little army men could also be baseball players. I had a tiny wooden bat and a round BB fishing weight that served as a baseball. I arranged them in their outfield positions based on their physiques, as some were stouter and stronger and others looked skinnier and speedier. I pitched the BB to the hitter whose little bat swung hard. The competition was intense. The team I favored always won. Winning was everything.

When my time for kindergarten came, Mom decided she would bypass the teacher who had falsely accused my brother. She enrolled me at The Little French School, a private preschool that she probably viewed as the budget version of a preschool that Jacqueline Kennedy would favor. To Mom, “French” meant refined and superior. She liked to watch Julia Child’s cooking show and also bought her cookbook, although Mom’s repertoire of family dinners did not grow to include a duck pâté or boeuf bourguignon.

On my first day at The Little French School, the cutting and pasting of colored papers, drawing with crayons, and enforced group napping did not appeal to me. I felt compelled to conform, but I knew that I was clearly underperforming compared to my peers, who seemed to relish arts and crafts. They also ate the white paste when the teacher wasn’t looking. I tried it, but I didn’t like it. I would’ve rather been home watching Captain Kangaroo, Shari Lewis with Lamb Chop, Warner Brothers cartoons, or orchestrating a fierce battle with my little men.

Instead of calling it The Little French School, they should have named it The Little Pretentious School because the teacher’s style seemed forced. She demanded complete silence when she spoke, yet none of her words were impressive — or even French, for that matter. I found the entire school environment strange and unnecessary. Not exactly an outcast, I was nonetheless timid, like a stranger going through the motions on the outer edge of preschool society.

When Mom dropped me off the next day, I stoically took my assigned seat like a good little soldier. It never occurred to me to put up a fight for a return to the comforts of home. I was surprised and grateful for my luck when I became friends that day with a boy named Peter. He needed someone to crawl through a barrel and go down the slide with him at recess in the playground. I was Peter’s foil without complaint.

That same day at the Little French School I noticed a girl across the room. She was a blonde princess and I became flood ed with inexpressible feelings for her. Just glancing at her was intoxicating. Her name was Maria, reminding me of the West Side Story record that Mom played, with a song sung by a guy who just met a girl named Maria.

I was no stranger to girls; I had an older sister. She was in the Bluebirds so the house was occasionally flooded with her Bluebird girlfriends. Sometimes I played with Annie Harden, who was my age, because our mothers were friends. I had a cousin Judy, one year older than me, whom I saw at every family holiday. I wasn’t dumbfounded looking at any of them, but Maria was different. I was completely in love with her.

I drifted off to sleep at night thinking only about Maria, romantically consumed by imagining our warm, everlasting love, sweeter than a French eclair. I looked at her so much that it was inevitable she would notice my staring. I had not prepared for the moment when our paths would finally cross at recess one day; I was following Peter to the boys’ end of the playground when I brushed by her, uncomfortably close. I was speechless, a bundle of nerves. Unlike me, she wasn’t going to let the moment go by.

“What are you looking at, Peanut Butter Face?” Maria scoffed. I was mortified.

When Mom picked me up that day after school, she knew that something was wrong. I was glum, listless, on the verge of tears. It took her only half the car ride home to coax out of me that someone had called me Peanut Butter Face, which I disclosed in a burst of tears. Mom was very sympathetic. She told me that my freckles were cute and that I was exceedingly handsome. And that she wasn’t saying so just because she was my mother, but rather because everyone she knew had told her that. She taught me how to say, “Sticks and stones…,” but I was worried that the Peanut Butter Face tag might stick. Telling Maria about sticks and stones wasn’t going to cut it.

Seeing that she had failed to brighten my mood, Mom suggested that the next time someone called me Peanut Butter Face, I could say, “Same to you, and more of it.” I had my doubts about that comeback too. So I just steered clear of Maria the next day and didn’t dare look at her or even in her direction.

Mom never knew that I loved Maria; no one ever knew. Maria never called me anything again, but I always felt leery of her and kept my distance. But my unrequited love didn’t stop. I drifted into sleep each night overwhelmed by romantic feelings, the song about just having met a girl named Maria playing over and over again in my head. I was enveloped by the warmth of my dream, wherein we would marry and forever rejoice in our love.

While Mom saw me pout and cry in the car that day and extracted the triggering taunt, she never knew the full story, and certainly not the depth of the emotions that caused my tears to flow uncontrollably. An insult could be conveyed— but not a love so pristine, perfect, and private that it was impossible to share.

HOME • ASSISTED PUBLISHING • JOIN MAILING LIST